The Frisch Africa Encounter

The next big thing that completely deconstructed the classroom was my Africa project, a month-long interdisciplinary unit that culminated in a night when students presented what they had learned to their parents and the Frisch community. You can read about that project here, where I discuss the overall program and launching it; here, which is a blog post about the evening; here, where I discuss my sister Smadar Goldstein's presentation on the integration of Ethiopian Jewry into Israeli society; and here, which is a reflection post about what my students got out of the unit.

It was really after the Africa program that the students and I realized we couldn't go back into the box of a normal English classroom. As loose as that box can already be, given the fact that English is based on discussion and a healthy amount of student opinion and discourse, even a normal English classroom is not the messy, sometimes chaotic, and exhilarating experience that we had had completing something like The Frisch Africa Encounter. I had to look for more ways to un-school school.

The Sophomore Renaissance Project

Here's a presentation, where you can see the background students learned about the Renaissance and Shakespeare's plays as well as the vocabulary words the students studied and the neologisms they created. Notice also that the students chose a target audience for their presentations and so had to gear their wording and information to that audience:

Shifting From Teacher-Produced Work to Student-Produced Work

The Sophomore Blog

10H Explorations

Here's a blog post I particularly like by a student who used art to reflect on what she had learned about women in the literary works and historical eras we studied throughout the year:

Nonconformist Women

What Kind of Final Would be Appropriate?

The sonnet papers were due on the last week of school, and I was debating what to do for the final. On the one hand, writing an essay or two on a final wouldn't be wrong. Students generally don't get enough essay writing practice. On the other hand, the class had been so liberated from a normal structure that I found the thought of giving a traditional essay final somewhat boring. It also didn't seem appropriate: here we had done all this non-traditional schooling; were we now going to go back in the box? I didn't even know if my students would agree to do so. After all, when we were reflecting on the year, the kids were making comments along the lines of "We want the classroom to be a place we learn in, not a place they [teachers] teach in." (How awesome is that comment, by the way?!)

When I posed the question of what to do for the final, the kids quickly revealed they felt as I thought they would: they didn't want to write an essay because they wanted something more out of the box. In fact, they outright said, "You took us out of the box; now you can't put us back in it."

Okay. Okay!

We spent two days of class debating what to do for the final. This decision-making process, of which the kids were a part, was very important to me, since it became part of the student-centered learning that I had been encouraging all year.

We still hadn't come up with anything when a chance comment in the hallway made me think -- don't ask me how; serendipity by design is sometimes, like a good joke, not worth explaining -- that a Twitter chat would be perfect as a way of culminating our year.

I pitched the idea to the class. Some were onboard right away; others were more skeptical, not sure of the technology and what exactly it would entail. After I explained to the kids what a Twitter chat was, we talked through what I'd require of them:

* participation in a conversation about the works they had read this year, including an outside reading book the kids had been assigned during the last quarter of school

We came up with abbreviations for the works, so the kids wouldn't have to use up too many characters in a Tweet. Here are our abbreviations:

CD: Candide

IE: The Importance of Being Earnest

CT: The Canterbury Tales

DH: A Doll's House

PB: The Poisonwood Bible

Different groups of students had read different Shakespearean comedies. Here are those abbreviations:

MidSum: A Midsummer Night's Dream

12Nite: Twelfth Night

MuchAdo: Much Ado About Nothing

Shrew: The Taming of the Shrew

* a good number of quality Tweets during the hour-long chat we'd have about literature; the Tweets needed to show their understanding of the works and how the works connected to each other as a whole

(During the final, the students expressed concern that they weren't responding fast enough. I told them to sacrifice some quantity for quality.)

We practiced chatting a little in class and worked out the kinks with the technology. I made sure all students had a device from which they could Tweet comfortably.

To deepen the experience of the final and give it more authentic purpose, I posted on JedLab, a Facebook group of over 700 Jewish educators [full disclosure: I am one of the group's facilitators], that I would be doing a Twitter chat as a final and asked anyone who was interested to join in our conversation. I particularly reached out to Ken Gordon, PEJE's social media manager and a bibliophile, since I thought he would be perfect for the "convo."

The Final

The Twitter chat was a perfect forum in which to showcase our work for the year. It was unusual and continued in the vein of being an un-schooled experience. There was no tension in the room as the kids "took their final"; there was just the excitement of seeing their thoughts show up in the chat and responding to each other. The students were laughing and chatting animatedly throughout the hour we tweeted, with my encouraging them and answering questions as they came up. How different this experience was from a tense and anxiety-producing exam!

|

| Michael wielding as many devices as he can in order to see and respond to Tweets! |

|

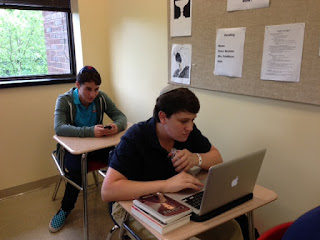

| A stack of books and a computer: we're ready for a 21st-century final! |

|

| Solomon tweeted this insightful comment: "If you aim for a perfect life, you'll get a full one." |

The addition of my educator colleagues to the conversation made the experience all the more meaningful for the students. Ken Gordon tweeted consistently throughout the hour, making the kids laugh with his insouciant comments but challenging them to support and develop their ideas. Yechiel Hoffman also joined our conversation, making the kids feel special about what they were doing by pointing out the uniqueness of the experiment. A few of my students at one point began shouting out that they were engaged in a debate with Adrian Durlester, another of my JedLab colleagues who joined the chat and got the kids thinking more deeply about their ideas.

|

| I liked seeing smiles on my students' faces during finals and not looks of panic and anxiety |

Want to See the Final?

I archived the final on TweetArchivist, and you can see the chat there. You can also view the interesting analytics and data I got from the final, such as who tweeted the most and which hashtags, other than our #10final, were used most frequently. Interestingly #satire showed up as a popular hashtag and that was because when I asked what genre had taught the kids the most about the world, satire or realistic fiction, satire won hands-down. Interesting!

Some Additional Observations

One day before the final, on her way out of class, I asked a student what she thought of the test. She said, "I get it. We're creating our final together," referring not to the way we had chosen the "exam" but to the fact that our final product would reflect the unique insights of each member of the class, woven together in the tapestry of a hashtag. The student understood one of the ethos of the class and of my teaching, one that I share with JedLab, which is that I want my students and all people to see themselves as creators. This student's response showed me she understood the larger, meta- goals I had been trying to accomplish in the course.

I think my student's insight also answers why I didn't have a discussion as a final, a question some colleagues asked me when I told them what I was planning. There is something concrete we created with the chat, not only because you can actually now read it, but also as it was going on. Anyone who has participated in a Twitter chat can tell you it's something different from a discussion, which is obviously still an important part of literature class and life. I've created a Professional Learning Network (PLN) on Twitter that has now, with JedLab, crossed over to Facebook; that network has formed because of chats I've had with a group of people who have the same concerns as I do. I've now met in person and have had phone and Google hangout conversations because of the connections I've made on Twitter.

When I spoke with Ken Gordon after the chat, he pointed out that now the students would know how to do the same kind of networking and relationship building, when the time was right.

Another thing that the Twitter chat could accomplish that a discussion could not is that it allowed there to be multiple conversations going on at once. I know, you're saying, "Welcome to my class on any given day," but in a chat that multiplicity is welcome and desired, while in a classroom it can cause chaos and a need for the teacher to do meditative breathing exercises after school. The different conversational threads occurring were another outcome I'd hoped would happen, and I was glad the kids became comfortable enough in the venue to engage in.

Finally, some logistics: I didn't need a proctor for my final, since I had to moderate it. And no one needed extra time. Let that one sink in.

"Final" Thoughts

As you can see from the archive, the kids tweeted things such as "so excited for English final" and "BEST FINAL" and created hashtags such as #likethisfinal. When the final was over, the students clapped and remained to discuss it. There was a palpable excitement in the room while the chat was going on and after, and we were all so happy -- to have taken a final!

I can't wait to see what my students will come up with next year as we continue our learning adventures and find new ways to challenge each other to think and explore.

Thank you to my PLN for making me see the power of Twitter and SM relationships and for enabling this final to be born and hatch.